By Katherine Malus

September 9, 2018

After years of negotiations to sign and comply with the JCOPA, the future of the treaty is uncertain.

Back in the 1950s,

when nuclear proliferation was seen as more of a goal rather than a problem, the United States helped Iran create its nuclear program through the United States Atoms for Peace Program. President Eisenhower intended for this program to help developing countries use nuclear power for energy and other peaceful purposes. The program also helped the United States secure allies during the Cold War.

Following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the relationship between Iran and the United States changed dramatically. After President Carter allowed the Shah, the ousted-Iranian leader, to receive medical treatment in the United States, a 15-month Iranian hostage crisis ensued. Even though Iran no longer received help with its nuclear program from the United States, nuclear development continued. Given the lack of open communication between Iran and much of the western world, some aspects of the Iranian nuclear program’s origins and capabilities remain a mystery to this day.

In 2015, China, France, Germany, Russia, the U.K., and the United States, also known as the P5+1, signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) or the Iran deal, signifying the first tangible effort of the United States and the other signatories to limit Iran’s nuclear development. Today, the JCPOA seems to have a bleak future, as President Trump decided in May of 2018 to pull the United States out of the agreement. While the debate about the JCPOA’s merits rages on, the future of Iran’s nuclear capabilities remains uncertain.

Pre-Revolution Nuclear History

During the Shah’s rule, through the United States Atoms for Peace Program, Iran received the United States’ help with nuclear technology, nuclear fuel, training, equipment laboratories, and power plants, all to be used for the generation of electricity and research. In 1967, Iran received its first 5 MW (megawatts) research reactor, known as the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR), powered by highly-enriched uranium (HEU). The reactor can produce up to 600 grams of plutonium a year and became the starting point for future multibillion-dollar contracts with other nations, including France, Germany, Namibia, and South Africa.

Kraftwerk, a German company, helped to complete one of the most significant projects for the country’s nuclear program. Built on the coast of the Persian Gulf, the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant was meant to hold two nuclear reactors; Kraftwerk nearly finished one reactor when the Iranian Revolution broke out.

In addition to receiving international help, the Shah insured home-grown nuclear development. In 1974, he established the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), charging it with a task of constructing 20 nuclear power reactors, a uranium enrichment facility, a reprocessing plant for spent fuel, and producing 23,000 MWe of nuclear power by the end of the 20th century. The Shah intended for the nuclear power to replace oil and gas, which could then all be exported and sold. For context, Iran produced 4,183,930 barrels or 175,725,060 gallons of oil in 1971, nearly 10% of the world’s total oil production.

During this time of nuclear advancement, Iran followed international nuclear standards that were in existence at the time. In February of 1979, with the Shah and his family already in exile, the Iranian Parliament ratified the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), agreeing to its goals to prevent proliferation of nuclear weapons, promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy, and eventually total disarmament.

Post-Revolution Nuclear History

The Iranian Revolution, which set up the new Islamic Republic on April 1, 1979, not only echoed in an era of dramatic change for the country but also its nuclear program. Leading up to and during the Revolution, many of the foreign and Iranian nuclear workers fled the country. The new leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, viewed the nuclear program as “un-Islamic” until 1984.

Due to the newly hostile American-Iranian relationship, Iran no longer received help from the United States and its allies, as the United States put pressure on countries that attempted to get involved in Iran’s nuclear program. Eventually, Iran made deals with Pakistan and China, but the United States blocked parts of the Chinese agreement that would have given Iran additional reactors. The United States successfully blocked many other Iranian nuclear contracts, forcing Iran to seek help from nations and actors Americans could not control.

Beginning in 1987, Iran received nuclear plans and imports, such as centrifuges, from unknown foreign entities. Many suspect that these originated from Pakistani scientist A.Q. Khan’s underground nuclear network, who is believed to have helped Pakistan, Libya, Iran, and North Korea advance their nuclear programs.

The countries involved in Khan’s network, in turn, helped one another with the nuclear technologies that Khan could not assist them with. Beginning in 1992, Iran entered into deals with North Korea, mainly involving missiles. North Korea provided Iran with missiles in exchange for more money for its missile program. Due to the antagonistic relationship that much of the western world has with these two nations, details of their exchanges are largely unknown.

Nuclear Weapons?

Many aspects of the Iranian nuclear weapons program and exchanges with undisclosed countries remain a mystery, but some facets have been revealed over time.

It is now known that Iran established its nuclear weapons program, known as Project Amad, in the late 1990s/early 2000s. The project entailed the acquisition and production of weapons-grade nuclear material, testing of nuclear weapon components, and planning for the construction of a unique nuclear weapon. The project appears to have ended suddenly in 2003. In 2011, the IAEA released a document containing all the information known about Project Amad at that time and explained that it remained unclear whether any remnants of the project, particularly those related to a nuclear explosive device, remained.

In April 2018, Prime Minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, announced that Israeli spies raided a nuclear information warehouse in Iran. According to the Prime Minister’s statement, the spies found documents that confirmed the existence of Project Amad, as was speculated by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and much of the Western World, despite Iran’s insistence that its nuclear program had always been peaceful.

The spies in the Israeli raid collected documents from 15 years ago, so their information only provided historical context for the extent of the project, rather than revealing the current status of the nuclear weapons program. According to Israel’s findings, Iran had made plans to build five nuclear weapons and to test them at different sites, suggesting that Iran was closer to a nuclear weapons program than previously thought. However, the problem with all this newly disclosed information is that it cannot be easily verified. Israel and Iran have had their own complicated history, and Israel used its findings to try and convince nations to back out of the JCPOA.

A Trail of Broken Agreements

Broken agreements and failed negotiations were all too common before the JCPOA. In 2003, Iran welcomed the IAEA through the signing of the Additional Protocol, which granted the IAEA information and access to Iran’s nuclear program facilities. This protocol also allowed the IAEA to use the most advanced technology to inspect all nuclear sites in Iran. Three years later, Iran backed out of this deal, following the IAEA’s discovery of undisclosed parts of the nuclear program, leading to American sanctions.

Right after its departure from the Additional Protocol in 2006, Iran announced the construction of new nuclear facilities expected to hold 2,784 centrifuges to enrich uranium. Four years later, Iran announced it could produce highly enriched uranium (HEU - uranium enriched to over 20%, or uranium containing at least 20% of Uranium 235), the minimum agreed enrichment necessary for the construction of nuclear weapons. Uranium only needs to be enriched to about 3 to 5% to be used for generating electricity in nuclear power plants, which qualifies as peaceful nuclear use. Right up to this point, Iran depended on other countries to obtain HEU.

Iran’s announcement regarding uranium enrichment sparked concern in the international community, leading to additional sanctions imposed on the country, and secret actions to halt Iran’s nuclear development. In July of 2010, a worm attacked 15 nuclear facilities in Iran, causing centrifuges to break. While it is clear that a cyber attack caused this worm, the actor behind the attack remains unknown.

Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)

Despite the cyber attack and the sanctions, Iran’s nuclear program continued to advance. Although Iran and other nations initiated some talks to slow Iran’s nuclear development, none resulted in formal agreements. It was not until June 14th, 2013, when Hassan Rouhani was elected President, that negotiations with Iran took a more promising turn. In one of his first speeches as President, Rouhani expressed his desire to negotiate with the P5+1 about the development of the nuclear program in Iran.

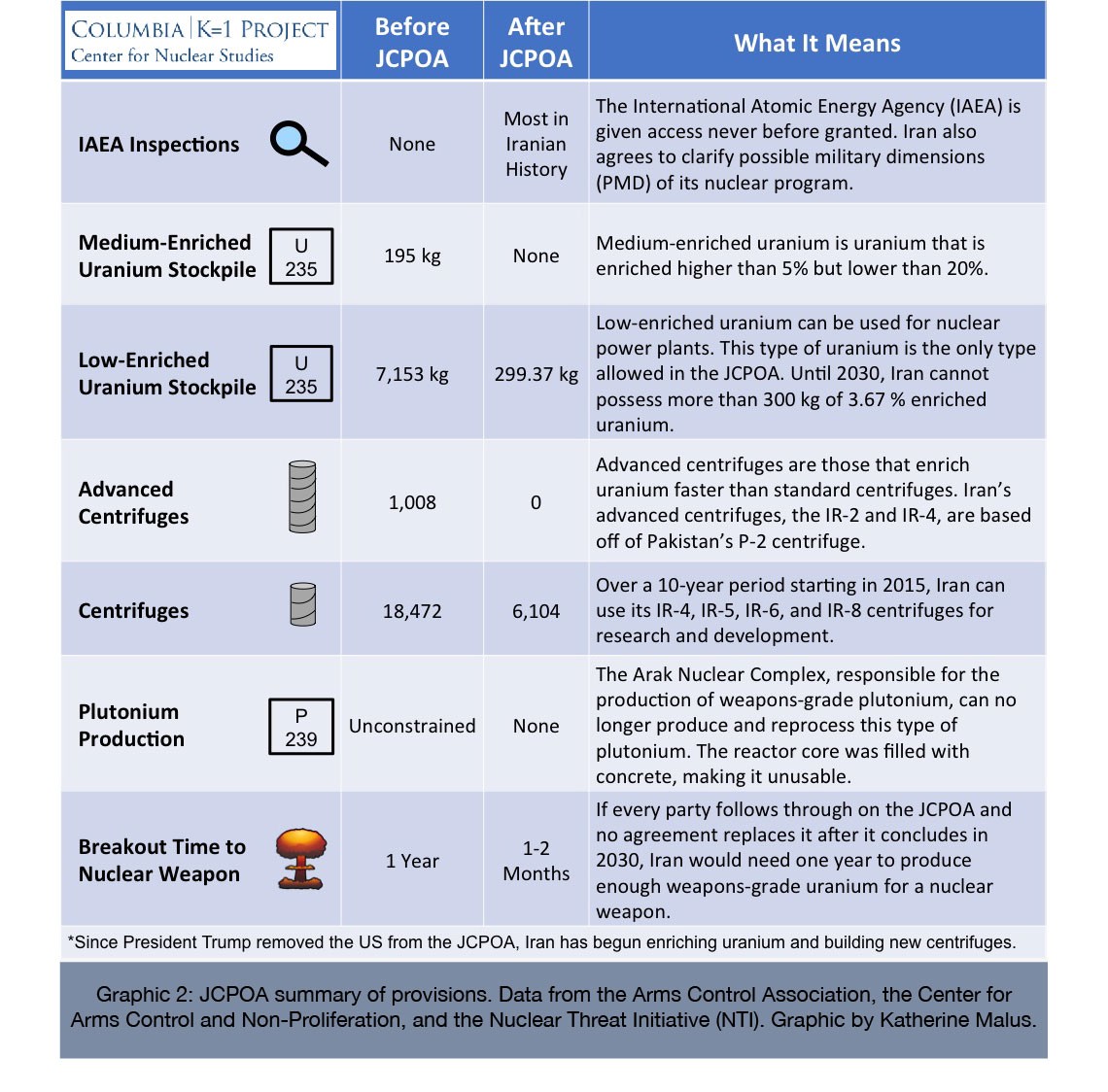

Negotiations came into full fruition on July 14th, 2015, with the signing of the JCPOA. The purpose of this agreement is to slow Iran’s progress towards the construction of a nuclear weapon by reducing or halting altogether certain uranium enrichment activities. The JCPOA limits Iran’s centrifuge construction, heavy water-related activities, and weapons-grade plutonium and uranium production possession.

While Iran has violated the maximum amount of heavy water, used as a moderator in nuclear reactors, it has followed the specified procedure for removing the excess from the country. Iran has also managed to stay at or below any other levels for other provisions in the JCPOA measured by the IAEA. Despite Iran’s seeming compliance, the deal remains in peril as the United States and Iran’s relationship grows increasingly hostile.

The main issue countries have with the agreement is that it does not cover the testing of missiles. Iran continues to test missiles, aggravating not only the United States but also the United Nations and other nations involved in the JCPOA. Since a missile is half of what is needed to have a nuclear weapon capable of threatening another country, this suggests that Iran may be using its nuclear program for non-peaceful purposes.

Others have issues with the sunset clauses in the JCPOA. Traditionally, agreements have these clauses which set up a date after which the terms of the deal conclude. In the case of the JCPOA, there are multiple sunset clauses pertaining to different parts of Iran’s nuclear program, such as uranium enrichment, the construction of centrifuges, and limitations on heavy water. In particular, most have a problem with the sunset clause pertaining to Iran’s uranium enrichment. According to David Phillips, Director of the Peace-building and Rights Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University, “The JCPOA was flawed from the outset because of the sunset clause. Iran is allowed to restart its enrichment of uranium after 15 years. That is much too short a period.”

Despite the issues with the agreement, many still take the position that since the JCPOA was already negotiated and decided upon, countries should follow the agreed terms to maintain accountability. Philips explained, “Once you negotiate a deal that is endorsed by the Security Council, you have to live with it. You can’t unilaterally walk away.” While many will continue to disagree about how to handle diplomacy with Iran, an Iranian nuclear program shrouded in mystery does not appear to be a promising path forward.

Relevant media

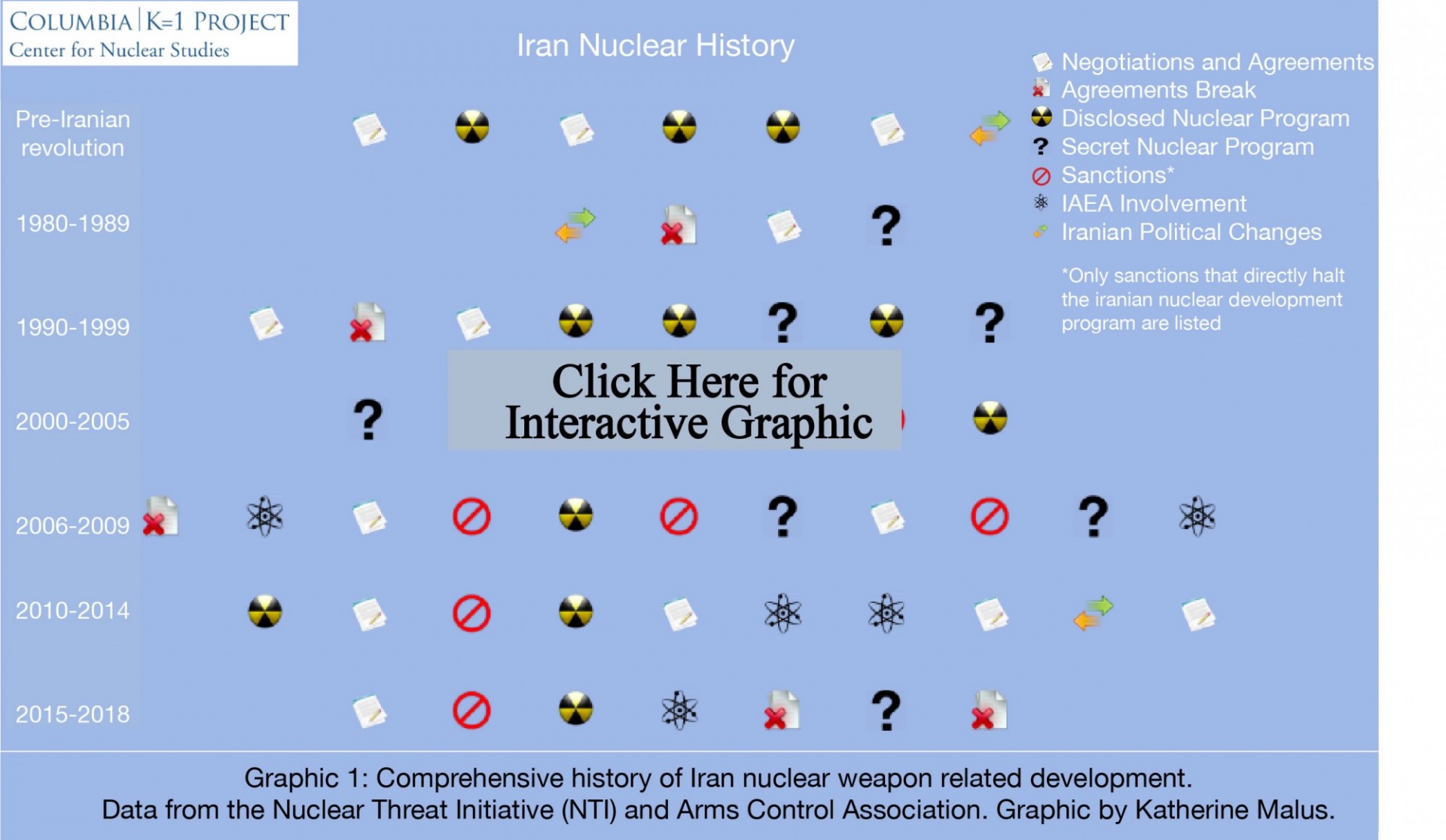

Downloadable data for Graphic #1, Comprehensive history of Iran nuclear weapon related technology.

Graphic: Interactive Map of Iranian Nuclear Facilities

Bibliography

Anderson, Raymond H. "Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, 89, the Unwavering Iranian Spiritual

Leader." The New York Times, 4 June 1989. The New York Times. Accessed 25 July 2018.

"Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP)." Nuclear Threat Intiative, 10 July 2017. Accessed 25 July 2018.

"Chronology of North Korea’s Missile Trade and Developments: 1992-1993." Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation

Studies (CNS), James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS). Accessed 25 July 2018.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. "Atoms for Peace Speech." International Atomic Energy Agency. Accessed 25 July 2018. Speech.

"Glossary." Nuclear Threat Intiative. Accessed 25 July 2018.

History.com Staff. "Iran Hostage Crisis." History.com, A+E Networks, 210. Accessed 25 July 2018.

Holloway, Michael. "Stuxnet Worm Attack on Iranian Nuclear Facilities." Stanford, Michael

Holloway, 16 July 2015. Accessed 25 July 2018.

"Iran." Nuclear Threat Initiative. Accessed 25 July 2018.

"Iran to Boost Uranium Enrichment If Nuclear Deal Fails." BBC, 5 June 2018. Accessed 2 Aug. 2018.

Laufer, Michael. "A.Q. Khan Nuclear Chronology." Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Accessed 25 July 2018.

"North Korea-Iran Nuclear Cooperation." Foreign Affairs, 2010. Council on Foreign Relations.

Accessed 25 July 2018. Excerpt originally published in Foreign Affairs.

"Nuclear Power in Iran." World Nuclear Association, Apr. 2018. Accessed 25 July 2018.

Perry, Jane, and Clark Carey. "Iran and Control of Its Oil Resources." Political Science Quarterly. JSTOR. Excerpt originally published in Academy of Political Science.

Ramzy, Austin. "Trump Threatens Iran on Twitter, Warning Rouhani of Dire ‘Consequences’."

The New York Times, The New York Times Company, 22 July 2018. Accessed 25 July 2018.

Sanger, David E., and Ronen Bergman. "How Israel, in Dark of Night, Torched Its Way to Iran’s

Nuclear Secrets." The New York Times, 15 July 2018. The New York Times. Accessed 25 July 2018.

"Table 11.5 World Crude Oil Production, 1960-2006." Geddis. Accessed 21 Aug. 2018.

"Tehran Research Reactor (TRR)." Nuclear Threat Initiative, 23 Aug. 2013. Accessed 25 July 2018.

"Timeline of Nuclear Diplomacy with Iran." Arms Control Association. Accessed 25 July 2018.

"Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)." United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Accessed 25 July 2018.