From the early years of the United States’ nuclear program, there has been a constant push to change and modernize the nation’s arsenal. Trillions of (today’s) dollars of government funding were poured over decades into projects ranging from the development of new weapon types to pioneering delivery systems. The current nuclear modernization plans and their associated costs have been described in a 2017 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report. After analyzing current and proposed plans through 2046, the year when the majority of ongoing modernization projects are set to be finished, the CBO projected that the thirty-year total cost would reach $1.2 trillion in 2017 dollars—$800 billion to “incrementally upgrade” the nation’s nuclear forces and $400 billion for direct modernization plans.

This spending is not set in stone and depends on the Congress’ willingness to continue to provide funding for each project in successive yearly allocation processes. Moreover, the 2017 report discusses a political reality determined by eight years of the Obama Administration, not the Trump Administration’s priorities, such as possibly restarting nuclear weapons testing and developing low-yield nuclear arms. Ultimately, the decision about investment in nuclear modernization is reached through a complex process involving work of executive branch agencies like the Department of Defense, the President’s yearly budget request, and Congress’ confirmation or denial of any particular monetary request. This means that the $1.2 trillion figure captures a moment in time—one possibility of what the true outcome may be.

This article details current plans to modernize each of the legs of the American nuclear triad—land and submarine based nuclear missiles as well as those launched from aircraft. It further provides perspective on the wider issues at hand by considering efforts to reduce spending and providing budgetary context.

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

The US currently retains 400 Minuteman III ICBMs spread over Air Force bases in Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota, with each missile expected to remain operational through 2030 following a multi-billion dollar service life extension. The Air Force has sought to replace the Minuteman III class ICBs with more than 600 missiles purchased through the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent program, which is intended to last through at least 2070. Recent Pentagon studies have pinned the total cost of this upgrade at $85 billion.

Some have questioned the value of this leg of the nuclear triad, in light of the continued operation of submarine-launched missiles and the nuclear bombers that make up the other sections of the three-part delivery systems. In particular, these analysts describe ICBMs as uniquely vulnerable to enemy attack due to their fixed position, as opposed to submarines and bombers, which are more mobile. Furthermore, ICBMs cannot be recalled or disabled once fired—raising the prospect of false alarm due to misguided intelligence reporting or technological failure.

ICBM advocates believe that maintaining this leg of the triad is key to providing continued options in case of a nuclear attack. Beyond the simple strategic value derived from another source of missiles, these supporters also point to the value of the location of ICBMs within the United States. While armed nuclear bombers and submarines can be targeted without a direct attack on American soil, destroying ICBMs would require such a strike. This raises the stakes of any engagement from an enemy and thereby provides deterrence in all but the most dire cases.

Submarines

The current American fleet consists of twelve Ohio class submarines (first deployed in 1981), each of which carries 20 Trident missiles. These submarines are currently expected to have a service life of at least 42 years—meaning that they will reach the end of this period within the next decade. Because of this, the Navy has begun to design and procure twelve Columbia class submarines that will begin to enter into service in 2031. This is the year that the first of the Ohio class submarines will have reached the end of their operations lifespan and been mothballed. Because of the lag in time between the deployment of the Columbia class and the retirement of the Ohio class, the full twelve ship force will not be whole again until the late 2030s, when a substantial number of the Columbia ships will have been built. In total, the program is projected at a cost of around $100 billion, which includes both the development period for the submarine plans and the building of the twelve submarines themselves.

Bombers

Modernization efforts for this leg of the triad mostly center around the Air Force’s development of the B-21 bomber. Unlike the submarine-based leg of the triad, the Air Force plans to maintain multiple separate types of bombers for the foreseeable future. Nearly one-hundred B-21 bombers, once they begin to enter service around 2025, will be complemented by B-52 bombers until 2040 and B-2 bombers until 2058. While the B-52 and B-2 bomber types are also able to deliver nuclear payloads, they last underwent major redesigns in the last part of the twentieth century and will be eventually phased out of service assuming that B-21s are produced as scheduled. All told, the total cost of developing and producing the B-21 could reach up to $80 billion—though this is highly dependent on how many bombers are actually produced.

New Missiles

In President Trump’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, he indicated that two new types of missiles would be developed to augment existing options. The first, a sea-launched cruise missile (to complement the already-existing air-launched cruise missile), would replace a previous sea-launched cruise missile that was retired in 2010.

A low-yield warhead that could fit onto the submarine-launched Trident missiles was also signaled to be in development. Since the Review was published, at least one of these warheads has been deployed aboard the USS Tennessee, with more presumed to be installed in the near future. These warheads carry an explosive yield of fewer than ten kilotons of TNT—considerably less than the other possible Trident warheads, which have yields of 90 and 455 kilotons and comparable to the power of the Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Efforts to Reform

In response to increasing costs associated with maintaining and modernizing the nuclear triad, Democratic representatives have introduced legislation intended to cut spending on nuclear weapons and delivery systems. In every legislative session since 2011-12, Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) has introduced a version of the Smarter Approaches to Nuclear Expenditures (SANE) Act. The bill includes provisions such as forgoing four of the twelve Columbia-class submarines and limiting total ICBMs to 150 from the current force of 400 and if enacted would cut nuclear-related spending by $175 billion.

Efforts to pass the bill—especially with a Republic-controlled Senate—have been largely unsuccessful. The most recent iteration of the legislation attracted only nine cosponsors between Markey’s version and the corresponding House of Representatives bill introduced by Representative Earl Blumenauer (D-OR)—eight Democrats and Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT), who caucuses with them.

Even if Joe Biden were to win the presidency in November, it is doubtful that cuts as drastic as those that Markey has proposed would be enacted. However, since congressional Democrats have been more willing to consider nuclear-related reform than their Republican counterparts, they could be emboldened by a progressive president.

Nuclear Spending in the Context of the 2021 Budget

The larger federal budget that President Trump proposed in February for the 2021 fiscal year contains provisions relating to nuclear modernization and upkeep in two distinct areas. The first is the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which oversees the nation’s nuclear stockpile and develops nuclear technologies as part of the Department of Energy. The agency was allocated $19.8 billion—an increase of over $3 billion from enacted 2020 levels and up from $12.9 billion in President Obama’s final proposed budget in 2017—of which $15.6 billion is directed to programs concerning nuclear weapons. This growth came even as the other areas of the Department of Energy’s budget request were lowered from $21.9 billion to $15.6 billion.

The proposed budget also allocates $28.9 billion to the Department of Defense’s nuclear program—money specifically focused on nuclear modernization and associated projects.

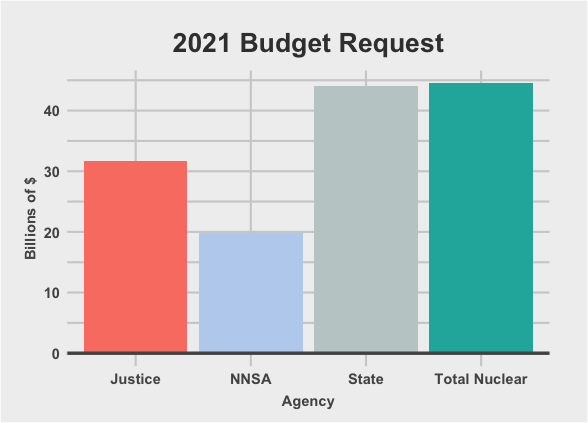

Taking the money given to the two agencies for weapons and delivery systems together, the $44.5 billion represents over 6% of the $671.5 billion in discretionary spending proposed to fund the nation’s defense and 3.5% of all discretionary funding. This total also outpaces the allocated budgets for nine cabinet agencies, including the Departments of State and Justice.

What does this mean for the future of American nuclear weapons?

Even in the face of potential disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic or domestic political situation, nuclear maintenance and modernization continues to be a top priority for the federal government. Spending has increased and is likely to continue to go up as new weapons or delivery systems in each leg of the triad come into service. While it is possible that a shifting international situation could shape the ways that this money is spent, the nearly century-old focus on nuclear weapons as a cornerstone of American national security appears entrenched and difficult to change.