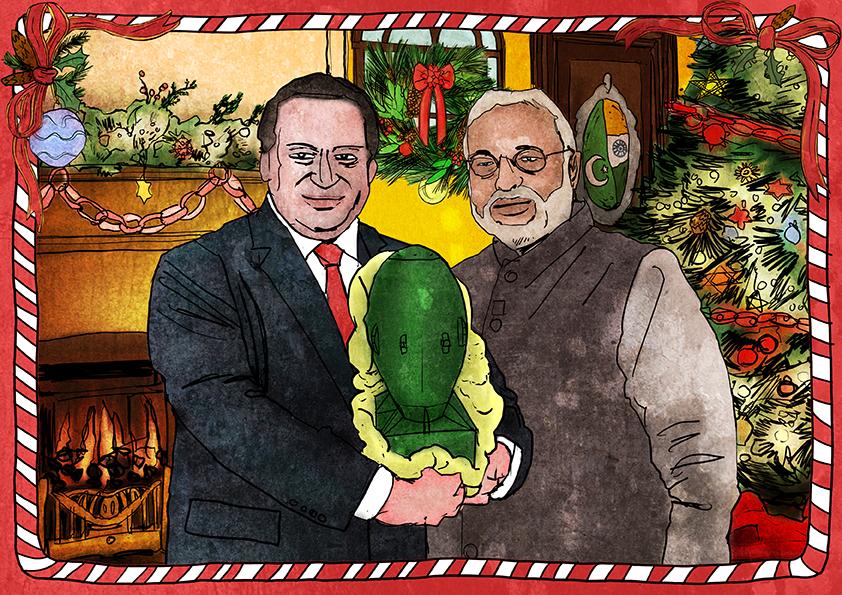

India and Pakistan are fierce rivals. And, they both have nukes.

The relationship between India and Pakistan

can be described simply as one of the fiercest national rivalries in the world. Despite the shared cultural, historic, geographic, and economic ties between the two nations, the India-Pakistan relationship has been marked by aversion and distrust since the partition of British India in 1947, resulting in the formation of the Union of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. While the nature of India-Pakistan conflict has been historical, religious, and cultural, a new dimension of the relationship emerged in the late 20th century: a nuclear dimension.

South Asian interest in the possession of weapons of mass destruction came about even before India had declared independence. In 1946, future Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru claimed that every nation would try to imitate the new atomic technology developed by the United States. While Nehru hoped for Indian science to develop atomic force for “constructive purposes,” Nehru also stressed that “if India is threatened, she will inevitably try to defend herself by all means at her disposal” (Ramana). India’s nuclear program officially started in 1944, still in the shadow of British rule, but even independence three years later did not spur India into making great scientific strides under the direction of Dr. Homi Bhabha and the Institute of Fundamental Research (Bhabani). Then, in 1962, after a concession of territory to China after a Himalayan border war, the Indian government revitalized the national nuclear program, citing that nuclear weapons could be crucial to engaging future Chinese belligerence (China had been developing nuclear weaponry since the First Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1954). By token, India refused to become a signatory to the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), citing the hypocrisy of first-world nations who would not reduce their nuclear arsenals after signing the treaty (Ramana). After a decade of research and constructive efforts, India detonated its first nuclear device in 1974, under the codename “Smiling Buddha” (Bhabani). With this action, India became the sixth nation in the world, and the first without a permanent seat on United Nations Security Council, to possess and detonate credible nuclear weapons of mass destruction.

The period bounded by Indian independence and the “Smiling Buddha” test was marked by a plethora of martial skirmishes between India and its Islamic neighbor, Pakistan. India and Pakistan fought three distinct wars in the period between 1947 and 1974: the First Kashmir War in 1947, over the states of Kashmir and Jammu, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, again over insurgency in Kashmir and Jammu, and concluding with the largest of the three conflicts, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, in conjunction with the Bangladesh Liberation War (Hewitt). The latter of the three wars lasted 13 days in total, but had dire consequences for Pakistan at the war’s denouement. The 1971 war resulted in Pakistan losing over 50,000 square miles of territory and millions of citizens to the newly birthed nation of Bangladesh, created with Indian assistance from the previous state of East Pakistan. With the loss of land and citizens, Pakistan had also lost much influence in South Asia, as well as support from its allies, the United States and the People’s Republic of China (Hewitt). A drastically weakened Pakistan took steps under Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto to elevate its fledgling nuclear program to martial heights, with the help of Pakistani scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project at Columbia University for the United States during World War II. Funding was provided by oil-rich Arab states, and more scientists were brought in to accelerate the program, inspired and motivated further by India’s primary detonation in 1974 (Strategic Security Project). Nearly two and a half decades later, Pakistan shocked the world by carrying out a successful nuclear test on May 28, 1999, becoming the seventh nation in the world to actively possess nuclear weapons.

The possession of nuclear weapons by both India and Pakistan marked the second distinct nuclear rivalry in the world, after that of the United States and the former Soviet Union. To the horror of the world, India and Pakistan entered the Kargil War in May of 1999, again over insurgency in Kashmir. This conflict, while ending peacefully a month after its inception, is the only example of direct warfare between two nuclear states. However, a much more serious incident occurred when two Pakistani terrorist groups opened a gunfire attack on the Indian Parliament on December 13, 2001. Twelve casualties (including the five gunmen) from the terrorist attack spurred India to increase military presence on the India-Pakistan border, prompting Pakistan to respond with an equal buildup (Hewitt). While martial casualties were never the result of direct warfare and rather resulting from artillery fire, the 2001-2002 India-Pakistan standoff proved significant due to the speculation of nuclear backlash. The Pakistani Prime Minister refused to renounce Pakistan’s right to engage India in nuclear warfare, while Indian leaders stressed that India would only use nuclear weapons in defense. Borders were vacated and nuclear tensions eased following a series of diplomatic talks in October 2002, thus ending the standoff (Stolar). Only the Cuban Missile Crisis eclipsed this incident of nuclear tension in world history.

Since then, relations between India and Pakistan have been inching ever so slowly to a more peaceful existence, with reduced hostility relative to years past. However, the territorial rivalry remains, and is likely to remain for far longer than we can speculate. India and Pakistan act as two roadblocks on the road to disarmament. No two nuclear nations are entwined as tightly as the two in discussion. Pakistan has claimed that it will not disarm weapons until major steps towards personal disarmament are taken by the United States, and has gone even further to claim that it will remain nuclear for as long as India does (Harris). India refuses to answer to what it considers hypocrisy – Western leaders pleading with nations such as China, India, and North Korea to disarm while taking no steps to do so for their own nations. However, hope for a future free of weapons of mass destruction remains. India, despite many failures of policy, still supports the negotiation of a worldwide disarmament policy that is universal, non-discriminatory, and verifiable, and continues to be one of the foremost leaders in international organizations in nonproliferation advocacy. Pakistan has taken strident measures to secure its nuclear arsenal from domestic terrorists, and awaits action from the first world on the subject of nonproliferation. What India must do, before focusing on a worldwide disarmament movement, is to normalize nuclear relations with its ever-present rival. Pakistan must welcome Indian advancements towards nonproliferation, or even initiate the process. A world less threatened by the threat of nuclear war cannot be sustained without crucial involvement from India and Pakistan. Even more promising, such a world can begin to form under the leadership of Asia’s biggest sub-continental rivals.

Further Reading

- Eswaran Sridharan, The India-Pakistan Nuclear Relationship: Theories of Deterrence and International Relations

- Zahid Hussain, Frontline Pakistan

- Sumit Ganguly, India, Pakistan, and the Bomb: Debating Nuclear Stability in South Asia

- Bruce D. Larkin, Designing Denuclearization: An Interpretive Encyclopedia

Bibliography

Bhabhani Sen Gupta. 1983. Nuclear Weapons? Policy Options for India, Sage, New Delhi.

Hewitt, Vernon. “Kashmir – The Unanswered Question.” History Today.

Ramana, M.V. “The Indian Nuclear Bomb – Long in the Making.” Tripod.

Stolar, Alex. “To The Brink: Indian Decision-Making and the 2001-2002 Standoff.” Stimson.

Strategic Security Project. “A Brief History of Pakistan’s Nuclear Program." FAS.