By Katherine Malus and Hilary Huaici

July 13, 2018

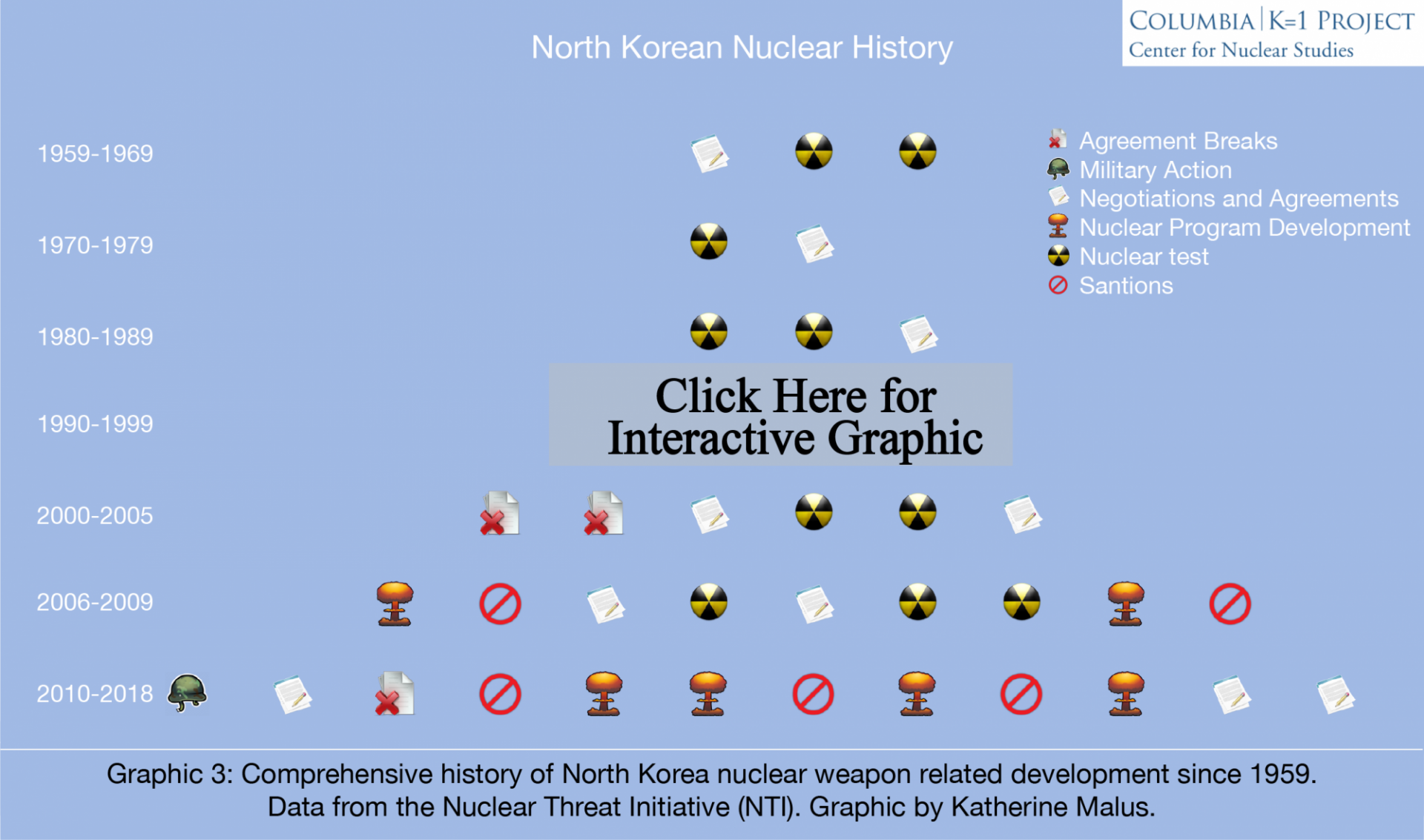

Will North Korea disarm? The country has intermittently entered into disarmament talks since 1992 and consistently broken previous agreements.

For the last few months,

nuclear weapons related developments from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), commonly known as North Korea, have dominated the news cycle. During this time, North Korea has significantly shifted its stance on its relations with South Korea and the United States.

On November 29th, 2017, North Korea claimed that it had successfully tested a missile capable of reaching the mainland of the United States. This news was quickly followed by condemnations and additional sanctions against the country. In April, nearly five months after the missile test, North and South Korea met for an inter-Korean summit, followed by an additional one in May. In June, the United States President Donald Trump and Chairman Kim Jong-un met in Singapore.

These recent summits seemingly legitimize and solidify Mr. Kim’s spot at a negotiating table dominated by discussions about nuclear weapons, begging the question of how North Korea became nuclearly relevant. North Korea’s nuclear history is a nearly sixty-year journey punctuated by technological advances and accompanying complex interactions with foreign powers.

Development of plutonium and uranium

For any country to develop a nuclear weapon capable of threatening any other country, it would need two pieces of technology. The first is the nuclear weapon itself - the ability to generate an explosion using fission or fusion power. The second is the development of a missile, which is a carrier for the nuclear weapon that allows the weapon to reach a target.

In 1959, during the height of the Cold War, North Korea and the Soviet Union signed the nuclear cooperation agreement, which informs most of North Korea’s nuclear knowledge and technology to this day. This agreement signified the official start of North Korea’s nuclear program.

With the assistance of the Soviet Union, North Korea began constructing a nuclear research center in Yongbyon, initially claimed to be intended for peaceful production of nuclear power, but shortly after its construction, North Korea began using the center for military purposes. By 1986, a 5 megawatt-electric Magnox gas-cooled reactor was built at Yongbyon, modeled after a British design with a dual purpose of producing electrical power and plutonium-239 for use in nuclear weapons. This type of reactor uniquely uses the more easily accessible mined uranium, which consists of 99.28% Uranium-238 and 0.7% Uranium-235, as fuel. At that time, both the Soviet Union and the United States used the partially enriched uranium, which has a higher percentage of Uranium-235.

The reactor operated until 1994, following the 1994 Agreed Framework, a deal between the United States and North Korea that stalled North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. The reactor was, however, turned on again in 2003, a year after North Korea exited the deal. The reactor produced approximately 6 kg of plutonium a year. For comparison, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)’s definition of possessing a Significant Quantity of plutonium is 8 kg. To date, experts estimate that North Korea possesses approximately 50 kg of plutonium. The critical mass of plutonium-239 is 5 kg.

Over the years North Korea also attempted to construct two additional Magnox-type nuclear reactors, the first of which could have produced an additional 60 kg of plutonium annually, and the second which could have produced 220 kg of plutonium annually. However, the country halted the construction of these reactors after North Korea agreed to be a member of the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) in 1985. As a signatory of the treaty, North Korea agreed to the the three NPT “pillars”: nuclear disarmament, nonproliferation, and solely civilian use of nuclear energy. By the time the country exited the NPT in 2003, and began to restart its nuclear program, the sites had deteriorated to such an extent that they were no longer usable.

The second type of fission material that could be employed in North Korea nuclear missiles is enriched uranium. The extent of the country’s uranium enrichment program is largely a mystery since the centrifuges are underground and more easily hidden from satellite photographs than reactors. Furthermore, uranium is mined from within the country. To produce a single nuclear weapon, a critical mass of 15 kg of highly enriched uranium is needed.

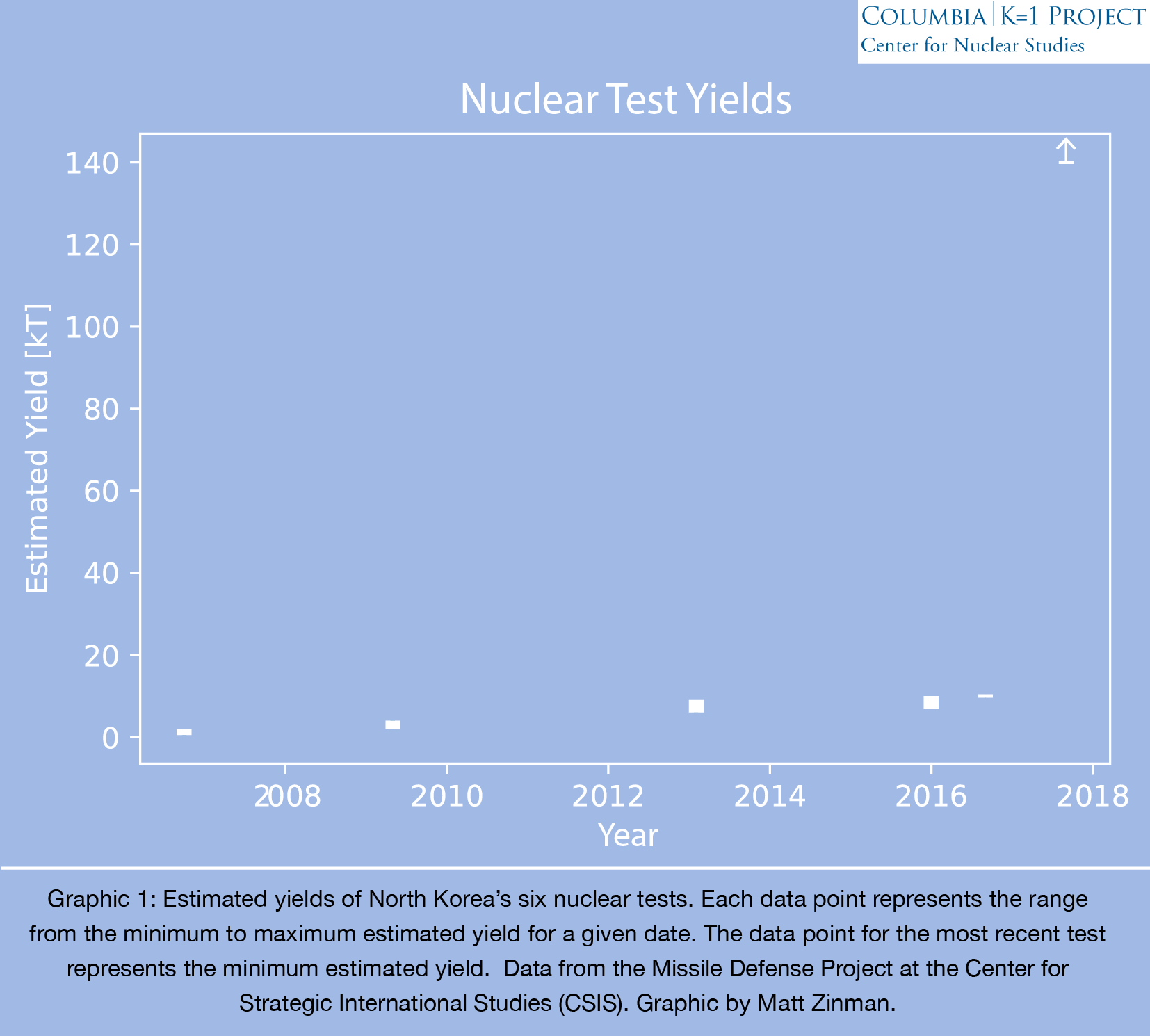

To test nuclear weapons, the country has constructed underground tunnels so that activity is not easily observable through satellite imagery. Estimates of nuclear test energy yields, however, can be made through detection of seismographic activity, as each blast sends a series of shockwaves through the Earth. To date, North Korea has conducted six nuclear tests, the latest of which was on September 3, 2017, as shown in the North Korea Nuclear Tests’ Yield Graphic below. The most recent blast resulted in a magnitude 5.7-6.3 earthquake, the largest nuclear test-induced earthquake since one of China’s tests in 1992. The North Korea government claimed that they had detonated a hydrogen bomb (where the fusion of hydrogen isotopes rather than fission cause the explosion).

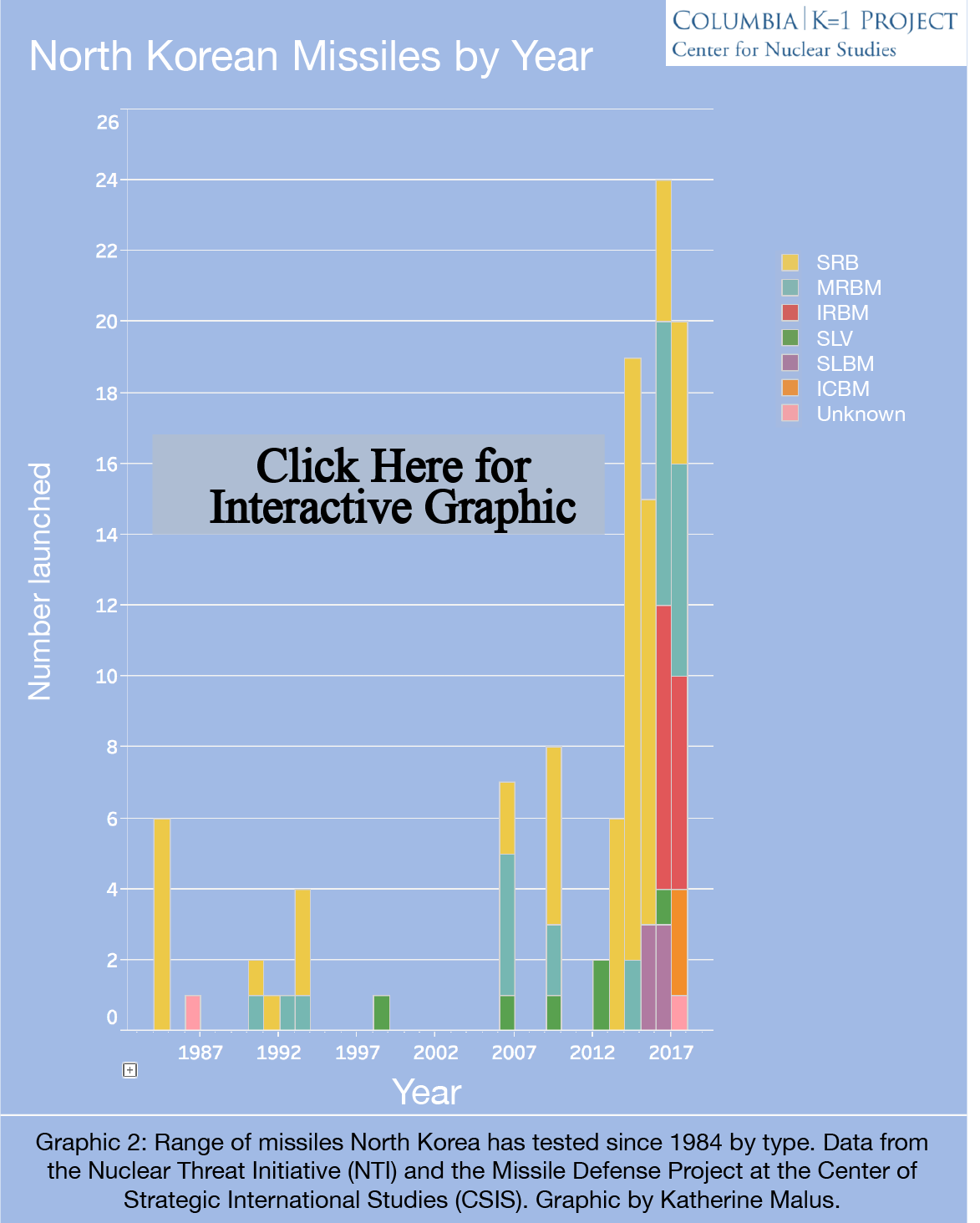

Development of missile technology

The second component of creating a nuclear weapon that can threaten other countries is the creation of a missile that can carry the explosive device to its target. Since its first successful launch of a satellite in 2012, North Korea has focused on the development of missiles capable of re-entering the atmosphere near the intended target. In 2017, the country attempted twenty missile tests, with varying degrees of success.

A remaining obstacle for North Korea’s development of this technology appears to be the size of the payload. The range and accuracy of a missile are both in inverse proportion to the size of the weapon it is carrying – that is to say, the larger the missile, the shorter its range and the less accurate its aim. Experts disagree on the extent to which it is currently possible for North Korea to mount a reasonably sized and sufficiently powerful weapon. Even though some past missile tests have been successful, they were conducted with no corresponding (nuclear) warhead mass attached.

Changes in Nuclear Policy

Regardless of the actual capabilities of these missiles, the country’s latest intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) test of the Hwasong-15, the first missile believed to be capable of reaching the entirety of the continental United States, caused a policy shift for the country. For the last few years, North Korea has faced crippling sanctions because of its unwillingness to negotiate with other nations or the United Nations. According to Professor Charles Armstrong, the Korea Foundation Professor of Korean Studies in the Social Sciences at Columbia University, “Kim Jong-un in November 2017 achieved what he said was his goal of nuclear deterrence with the test of an ICBM that North Koreans claimed could hit the US mainland with a nuclear weapon. It is not clear, according to experts, that they really can do that. But Kim Jong-un said that once they achieved that they would be willing to shift their priorities to the economy and talk to South Korea and the US, which they did at the beginning of 2018.”

On April 27th, 2018, President Moon Jae-In of South Korea and Mr. Kim met on the South Korean-side of the border town Panmunjom. This meeting marked the first between the leaders of the two nations since 2007. Leaders from North and South Korea had previously met with China, Japan, Russia, and the United States from 2003 to 2007 in what was known as the Six-Party Talks. By the end of these meetings, North Korea agreed to dismantle its nuclear weapons program, only to back out of the agreement in 2009. During the 2018 summit, President Moon and Mr. Kim signed the Panmunjom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula. In the third point of the Declaration, both countries agreed to “the common goal of realizing, through complete denuclearization, a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula.”

The two leaders met again on May 26th, shortly after President Donald Trump had canceled his scheduled meeting with Mr. Kim. According to Professor Armstrong, South Korea’s decision to have a second meeting to ease tensions between the United States and North Korea represents “the seriousness with which President Moon and his government are trying to achieve peace on the Korean peninsula. I think that the second summit meeting was very important in sending a message to the US. I think President Moon was saying that we Koreans, North and South, are going to go forward and work toward peace and it would be in your interest to get on board.” By June 1st, the summit between the United States and North Korea was rescheduled to its original date of June 12th.

President Trump had canceled the summit on the same day North Korea claimed to have destroyed its nuclear test site at Punggye-ri. Six nuclear tests had previously been held at the site, leading to suspicion that tests could no longer be held there. In three separate blasts, a network of underground tunnels, observation areas, and military buildings were destroyed. The North Korean government invited journalists, but no nuclear weapons inspectors, to document the destruction. Many suspect that the site can easily be rebuilt; nevertheless, this demolition was North Korea’s first active step towards denuclearization.

During the North Korea and the United States summit, President Trump and Mr. Kim signed an agreement focused on the historical gravity of the meeting. Nonetheless, the topic of denuclearization is includedin the third of four points: “Reaffirming the April 27, 2018 Panmunjom Declaration, North Korea commits to work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” The agreement document does not further define the term “denuclearization,” and has drawn attention from many critics for the lack of the word “verifiable.”

The United States’ dependence on North Korea’s previous negotiations with South Korea represents a shift in South Korean leadership’s work towards peace. According to Professor Armstrong, South Korea’s decision to have a second meeting with North Korea began this change: “there is a degree, which we perhaps have not ever seen, of South Korea really taking an independent position and a leadership position on the Korean peninsula.”

President Trump claims that after the agreement was signed Mr. Kim agreed to close a missile engine testing site. Since there has not been a timetable established for when and how North Korea will denuclearize, some have questioned the effectiveness of the meetings and the agreement. As Professor Armstrong said, these summits are “realistically the beginning of a process.”

Even though North Korea has had a circuitous path to the nuclear table, its current capabilities have ensured that the country keeps its seat. The path to disarmament will likely also be long and complex.

Related media:

Downloadable data for Graphic #3, North Korean Nuclear History.

Further reading:

The Nuclear Threat Initiative offers a comprehensive history of North Korea’s nuclear program.

Bibliography:

Associated Press. "North Korea Destroys Nuke Test Site in Front of Journalists." NBC News, NBC Universal, 24 May 2018. Accessed 13 June 2018.

Building the Global Seismographic Network for Nuclear Test Ban Monitoring. Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University. Accessed 19 June 2018.

"The CNS North Korea Missile Test Database." Nuclear Threat Initiative, 4 May 2018. Accessed 19 June 2018.

Davenport, Kelsey. "Chronology of U.S.-North Korean Nuclear and Missile Diplomacy." Arms Control Association, June 2018. Accessed 5 July 2018.

Haas, Benjamin, and Lauren Gambino. "North and South Korean Leaders Meet as US Indicates Summit May yet Happen." The Guardian, Guardian News and Media. Accessed 13 June 2018.

IAEA Safeguards Glossary. Vol. 3, 2001, Accessed 13 June 2018.

"Initial Actions for the Implementation of the Joint Statement." Nuclear Threat Initiative, Data collected from the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) and the Missile Defense Project at the Center for Strategic International Studies (CSIS). Accessed 3 July 2018.

Jensen, S. E., and E. Nonbol. Description of the Magnox Type of Gas Cooled Reactor (MAGNOX). Nov. 1998. International Atomic Energy Agency. Accessed 19 June 2018.

Kim, Max. "North and South Korea's Push for Peace." The Atlantic, Atlantic Monthly Group, 26 Apr. 2018. Accessed 13 June 2018.

Kristensen, Hans M., and Robert S. Norris. "North Korean Nuclear Capabilities, 2018." Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Accessed 19 June 2018.

Lui, Kevin. "Kim Jong Un Now Has Enough Plutonium to Make 10 Nuclear Warheads, a New Report Says." Time, 12 Jan. 2017. Accessed 13 June 2018.

McCurry, Justin, and Julian Borger. "North Korea missile launch: Regime Says New Rocket Can Hit Anywhere in US." The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 29 Nov. 2017. Accessed 13 June 2018.

"North Korea." Nuclear Threat Initiative, Accessed 13 June 2018.

"North Korea Announced Nuclear Test." CTBTO, 23 Apr. 2013, Accessed 5 July 2018.

"North Korean Missile Launches & Nuclear Tests: 1984-Present." Missile Threat CSIS Missile Defense Project, enter for Strategic and International Studies, 29 Nov. 2017. Accessed 5 July 2018.

"Panmunjeom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula." Arms Control Association. Accessed 13 June 2018.

Rosenfeld, Everett. "Read the Full Text of the Trump-Kim Agreement Here." CNBC, 12 June 2018. Accessed 13 June 2018.

Sevastopulo, Demetri, and Robin Harding. "Trump Says North Korea No Longer a Nuclear Threat." Financial Times. Accessed 13 June 2018.

Song, Hilary Huaici. "Nuclear Weapons 101: Back to the Basics." K=1 Project Center for Nuclear Studies Columbia University, Columbia University, 7 Dec. 2017. Accessed 5 July 2018.

"US-DPRK Agreed Framework/Six-Party Talks." Nuclear Threat Initiative. Accessed 13 June 2018.

"Weapon Materials Basics (2009)." Union of Concerned Scientists Science for a Healthier Planet and Safer World, Union of Concerned Scientists, Aug. 2004. Accessed 13 June 2018.

"Weapons of Mass Destruction Conventional Arms Regional Disarmament Transparency and Confidence-building Other Disarmament Issues Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)." United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA), United Nations. Accessed 5 July 2018.

Williams, Jennifer. "Read the Full Transcript of Trump’s North Korea Summit Press Conference." Vox, Vox Media, 12 June 2018. Accessed 13 June 2018.

Icons for Graphic 3 were extracted from: https://www.freeiconspng.com. Image numbers: 30059,19308,713, 36542, 25272, and 13412.