By Katherine Malus

November 2, 2018

In 1945, the United States - for the first time in history - used nuclear weapons to attack another country. An arms race that lasted decades began almost immediately after these attacks, and many, including former Secretary of Defense Bill Perry, are concerned that we are currently entering into another arms race. Despite the continuingly heightened risk of a nuclear attack occurring on American soil, the United States and its citizens remain largely unprepared for a nuclear disaster.

When the Cold War

ended nearly three decades ago, the Doomsday Clock was set to 17 minutes to midnight. The Clock, designed in 1947 by artist Martyl Langsdorf and set by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, signifies how close the world is to a “nuclear apocalypse.” For the first time since 1953, the world is two minutes away from nuclear destruction.

While the world has faced the Clock’s proximity to midnight before and lived to see the minute hand move backward, the world - and thus the Clock - is currently influenced by a number of different factors that did not exist in 1953. Perhaps the newest and most relevant is the higher probability of a nuclear weapon falling in the hands of a terrorist group or rogue state, such as Iran or North Korea, as opposed to a nuclear attack by another recognized nuclear weapons state. As Dr. Irwin Redlener, a professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, explained: “the rogue state and the terrorist detonation remain a possibility and should be considered among the most serious disaster threats that the United States faces.” Despite the reality of such a nuclear attack, the United States remains largely unprepared.

U.S. History of Nuclear Disaster Preparedness

Today, fallout shelter signs, such as the one below, represent remnants of the nuclear disaster preparedness plans that the United States government intermittently encouraged or funded during the Cold War, from the 1950s through the 1980s.

In 1950, United States Congress created the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA), to guide states’ actions in regards to civil defense policy. As such, FCDA was largely responsible for the first nuclear shelters.

In 1952, the FCDA - with the help of the Ad Council - created nine different short films about preparedness. These films included the famous Duck and Cover drill with Bert the Turtle, which portrayed students saving themselves from a nuclear attack by hiding underneath their school desks. Today, these films are seen as ill-informed, and even were used to make a 1982 satirical film, Atomic Cafe, about the misinformation the United States government gave to American soldiers and citizens in the early years of the Cold War.

During the early 1950s, the FCDA also encouraged Americans to begin building at-home nuclear fallout shelters. Each shelter was supposed to have at least two weeks of supplies, the recommended amount of time for staying in the shelter after an attack. At the time, however, Congress and the Executive Branch did not directly support this initiative due to the prohibitive cost of creating a system of nuclear fallout shelters across the country.

Following the Soviet Union’s test of the hydrogen bomb in 1953 and the release by the United States of the effects of its first thermonuclear bomb (“hydrogen bomb”) test, Mike, detonated in the Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands in 1952, the Eisenhower administration determined that shelter programs were no longer effective and instituted evacuation plans instead. Both hydrogen bomb tests’ effects seemed to convince the public that it was not possible to survive a nuclear detonation, unless people were warned in advance of the attack. Evacuation planning over shelter planning was, though, only proposed by the FCDA until March 1954, right after the United States tested its most powerful hydrogen bomb, Castle Bravo. Bravo was tested on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands and had a yield 1,000 times higher than the Hiroshima bomb. The testing resulted in severe radioactive contamination of numerous islands, which continues to impact the Marshallese society today. This occurrence led Congress and the FCDA to determine again that shelters were necessary for citizens’ protection.

The FCDA proposed a National Shelter Policy, which according to Homeland Security would have cost around $32 billion. The necessity of this policy was supported by the Gaither Report, commissioned by President Eisenhower in 1957, and, the Rockefeller Report in 1958, lead by Henry Kissinger. Evidence presented in these two reports, though, was not enough for President Eisenhower, who refused to take action towards enacting the policy. Instead, he replaced the FCDA with the newly created the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization (OCDM), which eventually became the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) and the Office of Emergency Planning (OEM).

With the election of a new president, John F. Kennedy, shelters resurfaced as an important element of civil defense against a nuclear attack as the United States government directly advocated for and funded nuclear fallout shelters. In September of 1961, The Community Fallout Shelter Program began, following an extensive survey to determine shelter locations. Each shelter had to be able to serve at least fifty people, who were given a storage space of 1 cubic foot. The program set out to supply local shelter sites with materials to defend against the effects of radiation. The OCD allocated water drums, food rations, sanitation kits, medical kits, radiation detectors, and package ventilation kits to each of the shelters, which were directly run and maintained by local government’s civil defense offices. In October, Kennedy asked Congress to allot $100 million to create public fallout shelters across the country. By the end of 1961, the Department of Defense had created a 46-page booklet about the shelters, including instructions of what to do if a nuclear attack occurred. These booklets were distributed to post offices across the country. According to the Department of Homeland Security, by the end of 1963, nine million public shelters had been identified and supplied.

On October 6th, 1961, President Kennedy also encouraged American families to begin building private nuclear bomb shelters in their homes. This effort arguably proved less successful than the public shelters effort, since only about 1.4% of American families implemented President Kennedy’s message.

During President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration (1965 to 1969), the shelter program and civil defense initiatives began to suffer. The Vietnam War drew money away from these preparedness programs and initiatives, and the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) became more popular. If a country decided to initiate a nuclear attack on another country, both countries would end up annihilated based on this theory of deterrence and retaliation.

Initiatives to directly protect civilians did not re-emerge until President Gerald R. Ford’s administration. The 1974 Crisis Relocation Plan (CRP) created evacuation routes for those who lived in the cities to escape to rural areas. Unfortunately, CRP had many flaws, since multiple days notice of an attack would have been required for it to work effectively. Additionally, urban infrastructure would not have supported mass evacuation from cities.

Preparedness for a nuclear disaster became a top priority for a final time under President Ronald Reagan’s administration (1981 to 1989). Following the creation of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) under President Jimmy Carter, President Reagan made nuclear disaster preparedness plans and evacuation routes a top priority, by asking Congress to allocate $4.2 billion for civil defense spending. While congress only allocated $147.9 million to the cause, this push for civil defense nuclear planning became the last of its kind to this day, following the end of the Cold War shortly after the end of the Reagan administration.

U.S. Nuclear Preparedness Today

In the post- Cold War era (1991- today) the United States, along with other nations, faces a new kind of nuclear threat. During the Cold War, the United States’ main nuclear opponent was the Soviet Union. Today, the United States faces a threat of a nuclear disaster not only from other countries, such as North Korea, Iran, or other rogue nations, but also from terrorist groups, who could easily access the materials and information necessary to construct a nuclear weapon. In addition, one cannot dismiss the possibility of a disaster stemming from accidental use of weapons currently in the United States’ own arsenal or other countries’ arsenals.

One threat facing the world today is missing weapons-grade materials from the old Soviet nuclear stockpile. In order to build a nuclear weapon, one would need plutonium (Pu 239) or highly-enriched uranium (HEU), uranium with a concentration of U235 higher than 20%. During unstable economic times, former Soviet nuclear personnel used to sell HEU on the side. The Soviet Union never created an inventory list of its nuclear materials, so most of the material that was and is stolen during and after the Cold War isn’t known to be missing. Between 1991 and 2002, there were fourteen confirmed cases of theft of weapons-useable nuclear material from Russia’s nuclear stockpile. Russia currently has 680 metric tons of HEU, over half of the total amount that exists in the world. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), a significant quantity of HEU, meaning “the approximate amount of nuclear material for which the possibility of manufacturing a nuclear explosive device cannot be excluded,” is 25 kg or 55.1 lbs. Since Russia does not disclose its plutonium stockpile to the IAEA, it is unknown how much the nation currently possesses. According to the IAEA, a significant quantity of plutonium is 8 kg or 17.6 lbs.

The uncertainty surrounding unguarded weapons-useable nuclear material is not limited to Russia. In 2007, six nuclear warheads were accidentally flown from an Air Force Base in North Dakota to Louisiana. The warheads were missing for 24 hours before officials in Louisiana discovered the error.

According to the Federation of American Scientists, there are over 14,000 declared nuclear warheads in the world today, and given the yet to be successful intentions for a world free of nuclear weapons, the threat of a nuclear disaster still looms large. As Dr. Redlener states: “There is no putting the toothpaste back in the tube here. …. I cannot imagine circumstances where we can get verifiable information of elimination of all nuclear weapons on the planet. I think we do have to come to grips with that … and make sure that we have done everything possible to control any situation that might result in a nuclear detonation.”

The United States and its citizens are not currently prepared for the after effects of a nuclear disaster of any type, whether an air missile from another nation, an attack on the ground from a terrorist or terrorist group, or some kind of accidental detonation. Dr. Redlener identified six cities that have the greatest likelihood of being attacked: New York, Chicago, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Houston. Only New York, Washington D.C., and Los Angeles’ emergency management websites give ways to respond to a radioactive disaster. Washington D.C. and Los Angeles’ websites directly address the possibility of a nuclear attack.

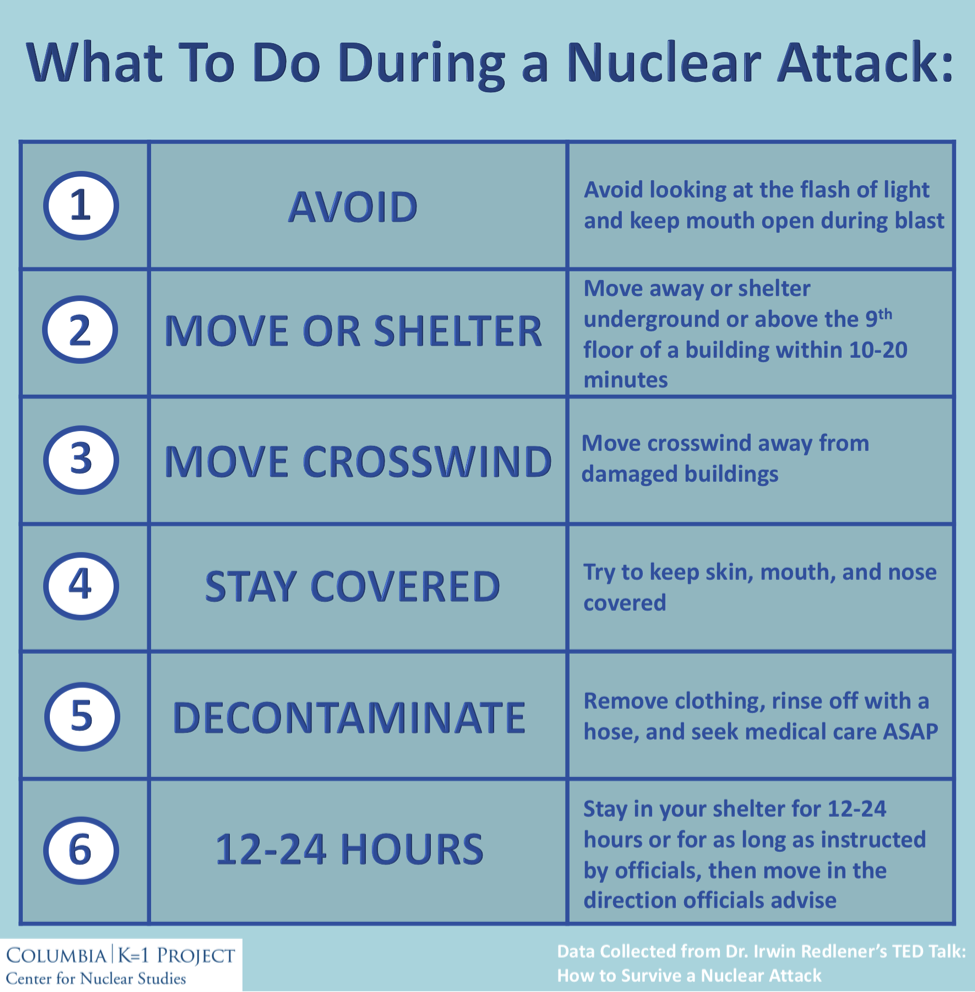

While it may seem unlikely that a person could survive a nuclear attack, there are seven simple actions that one can take to save his or her life - assuming that one is far enough (more than .5 miles away) from the core of the explosion. They are: (1) Do not stare at the light from the flash because it will blind a person instantly, and keep your mouth open to handle the pressure released from the initial blast. (2) Decide to move ten to twenty minutes walking distance away from the blast site or seek shelter either below ground or above the 9th floor of a building, to avoid the effects of fallout from the mushroom cloud. (3) Move crosswind from damaged buildings if you choose to leave, but only for 10-20 minutes. (4) Keep your mouth, skin, and nose covered as much as possible. (5) Remove your clothes, rinse off with a hose, while holding your breath. Seek medical care if possible. (6) Stay in the shelter for 12-24 hours after an attack to avoid the initial massive amount of exposure to radiation after a nuclear attack, or as long as instructed by the government. Only leave shelter once you know the direction to move.

Despite the fact that cities and citizens remain unprepared, research has been done on the effectiveness of these steps. According to Dr. Redlener, “ Brooke Buddemeier at Livermore National Labs in California has done a great deal of research on this subject [nuclear preparedness and survival]. He suggests that if a single-weapon detonation occurred in New York City, some 200,000 or more lives could be saved, if people knew how to protect themselves. That means knowing how and when to find adequate shelter and when it’s safe to leave the shelter.”

In order for these steps to be as effective as Buddemeier’s research suggests everyone would need to know them before an attack occurred. According to Dr. Redlener, “It’s all about understanding and following the basic message: Get as far away from the blast as you can in the first 10 – 20 minutes after the flash of light and explosion, go to a safe shelter, away from windows with lots of shielding between you and the outside and stay there for 12 – 24 hours or until officials say it’s safe to exit. Make sure you have a battery operated radio in order to receive those messages!” But as Dr. Redlener points out, “even getting that message out there is something that, if it was going to be effective, it would have to be repeated multiple times and with lots of reminders going out overtime. You would need a campaign, and posters, and public service announcements, elected officials talking about it. I don't think that anyone is in the frame of mind to do that.”

Before the world can become nuclear-free, it has to become nuclear-conscious, which requires work. Nuclear weapon states need to become more accountable for their stockpile and have a greater sense of urgency in achieving a nuclear-free world. In the meantime, governments need to work to prepare their citizens for a nuclear detonation through a collective effort to disperse accurate information on how to stay safe - or as safe as possible - during an attack.

Related Media

- How To Survive a Nuclear Attack TED Talk by Dr. Irwin Redlener

- Nuclear Terrorism: The Threat is Real by the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI)

- Teaching With Documents: Photographs and Pamphlet About Nuclear Fallout. National Archives.

Further Reading

- Americans at Risk: Why We Are Not Prepared for Megadisasters and What We Can Do, by Irwin Redlener.

- This Is What a Nuclear Bomb Looks Like by the New Yorker

Bibliography

“Air Force Fires Commanders over Nuclear Mix-Up.” Reuters, 19 Oct. 2007. www.reuters.com.

Bordner, Autumn S., et al. “Measurement of Background Gamma Radiation in the Northern Marshall Islands.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, no. 25, June 2016, pp. 6833–38. doi:10.1073/pnas.1605535113.

Chenault, William W. "Crisis-Expectant Planning for Crisis Relocation." Oct. 1981. Accessed 26 July 2018.

City of Chicago :: Supporting Info. Accessed 6 June 2018.

Civil Defense Museum-Community Shelter Tours Main Page. Accessed 6 June 2018.

CNN, Sam Petulla. “Where Are the World’s Nuclear Weapons?” CNN. Accessed 6 June 2018.

Civilian HEU: Russia | NTI. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Dhs Civil Defense-Hs - Short History.Pdf. Accessed 10 July 2018.

“Doomsday Clock.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Fallout Protection What to Know and Do.Pdf. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Fernandes, Cassandra Lee. "Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty." K=1 Project Center for Nuclear Studies, Columbia University, 13 Dec. 2017. Accessed 26 July 2018.

Gray, Andrew. "Air Force Fires Commanders over Nuclear Mix-Up." Reuters, 19 Oct. 2007. Accessed 26 July 2018.

Houston’s Hazards – Office of Emergency Management. Accessed 6 June 2018.

"IAEA Safeguards Glossary." International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 2001. Accessed 26 July 2018.

Illicit Nuclear Trafficking in the NIS | NTI. Accessed 12 July 2018.

“Kennedy Urges Americans to Build Bomb Shelters - Oct 06, 1961.” HISTORY.com. Accessed 6 June 2018.

Nuclear Blast | Ready. Accessed 6 June 2018.

"Nuclear Preparedness." Hawaii.gov, State of Hawaii, 13 Apr. 2018. Accessed 26 July 2018.

Nuclear Terrorism - FAQs. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Nuclear Terrorism Threat | Nuclear Weapons & Terrorist Threats | NTI. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Nuclear Vault. Duck And Cover (1951) Bert The Turtle. YouTube. Accessed 11 July 2018.

Our Hazards | Department of Emergency Management. Accessed 6 June 2018.

Plan for Hazards - Hazardous Materials Chemical Spills Radiation - NYCEM. Accessed 6 June 2018.

Petulla, Sam. “Where Are the World's Nuclear Weapons?” CNN, Turner Broadcasting Systems, 25 Sept. 2017. Accessed 26 July 2018.

Preparing for Nuclear Incidents | Emergency Management Department. Accessed 6 June 2018.

Redlener, Irwin. How to Survive a Nuclear Attack. TEd. Accessed 6 June 2018.

Security Resources Panel of the Science Advisory Committee. "Deterrence & Survival in the Nuclear Age." 7 Nov. 1957. Accessed 26 July 2018.

“Russia.” International Panel on Fissile Materials. Accessed 12 July 2018.

“Russia’s Use and Stockpiles of Highly Enriched Uranium Pose Significant Nuclear Risks.”Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, 12 Sept. 2017.

Vale, Lawrence J. The Limits of Civil Defence in the USA, Switzerland, Britain, and the Soviet Union. Palgrave Macmillan, 1987.

When Home Fallout Shelters Were All the Rage. 7 Oct. 2010.