Is the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty bringing us closer to a nuclear-free world?

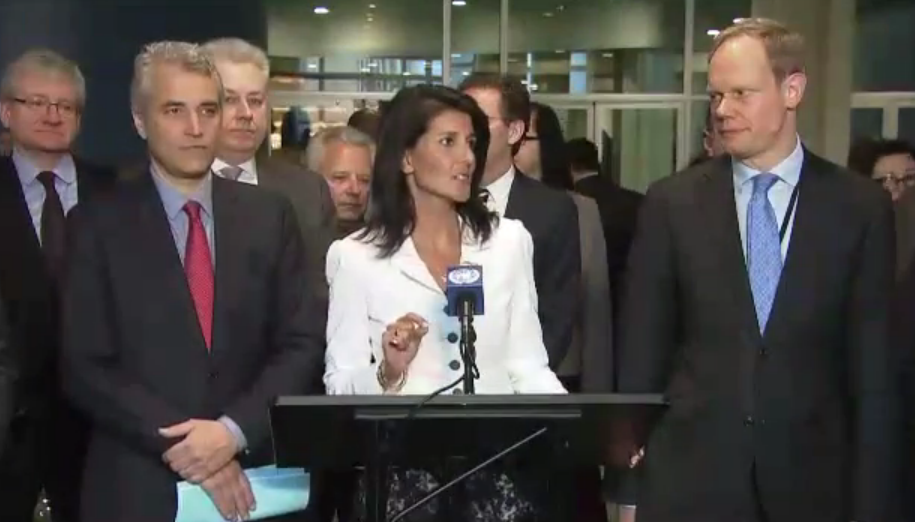

Earlier this year, the United Nations General Assembly convened to negotiate what would become the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The treaty, also called the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty, was adopted on July 7th 2017, and seeks to move the world towards a nuclear weapons-free future. In October, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to make the treaty happen and drawing “attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons.” Although many nations, including the United States, Britain, and France, boycotted the treaty at the UN convention, and none of the nine world’s nuclear-weapon states (United States, Russia, United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea) partook in the negotiations of the treaty, the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty marks a symbolic shift towards the total global prohibition of nuclear weapons.

At the UN vote in July, 122 states were in favor of the Nuclear Weapon Ban, while 69 nations did not vote. Provisions of the ban coincide with existing international law, including the UN Charter, international humanitarian law, and human rights laws. The ban was supported by many countries, including Austria, Ireland, Mexico, Brazil, South Africa and Sweden, along with hundreds of nonprofit organizations that are part of ICAN. South Africa, who formerly possessed a nuclear arsenal but eliminated the weapons voluntarily in the early 1990s, also voted in favor of the ban. While none of the nuclear weapons states offered support for the treaty, the Netherlands, the only NATO member to participate in the treaty negotiations, was the sole nation to vote against the agreement. Japan, the only nation to have suffered a nuclear attack, voted against the Nuclear Ban.

Of the nine states currently possessing nuclear weapons, only five are recognized in the earlier Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), which calls for the gradual elimination of nuclear weapons and for nuclear weapon states to “pursue negotiations in good faith”. In their joint statement against the recent Nuclear Ban Treaty, the U.S, U.K, and France reaffirmed their commitment to a gradual disarmament as outlined in the NPT. However, many non-nuclear states have expressed discontentment with both the slow progress of disarmament and the NPT’s vague language, which allows nuclear states to set their own pace of nuclear weapon reduction. By contrast, the Nuclear Ban Treaty is the first multilateral nuclear disarmament treaty concluded in over 20 years, and unlike the NPT, it provides for a “time-bound framework for negotiations leading to the verified and irreversible elimination of its nuclear weapons program.” In addition to providing a more concrete timeline for disarmament, proponents of the new treaty believe it will increase the stigma associated with a country’s possession of nuclear weapons, thus impacting public opinion.

Nations that have failed to support the ban argue that nuclear weapons deter conventional war, and that the ban does not address security concerns that could arise from completely eliminating nuclear weapons. According to the joint statement of the U.S, U,K, and France against the treaty, "…[The} purported ban on nuclear weapons that does not address the security concerns that continue to make nuclear deterrence necessary cannot result in the elimination of a single nuclear weapon and will not enhance any country’s security, nor international peace and security," and these nations do not intend to sign, ratify or ever become party to it. They argue that nuclear deterrence has allowed the world to avert global war for more than 70 years.

The Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty will enter into force 90 days after 50 countries have ratified it. As of September 22, 2017, although 53 states had signed the treaty, only Guyana, Holy See, and Thailand had ratified it. In the international system, the process of entering a treaty into law includes a process of adopting, signing, and then ratifying the document. Signing is not a legally binding obligation but simply demonstrates a state’s intentions to consider ratification. Ratification legally binds a state to the agreement, and typically requires a country’s legislative body to vote in support of the agreement. For example, in order for the US to ratify any international treaty 67 Senators need to vote in favor of it. Should the minimum number of countries ratify the Nuclear Ban Treaty and allow it to enter into force, then the countries with a nuclear arsenal would be in interference with international law.

The nuclear ban itself may not eliminate nuclear weapons, but it serves as a call to get nuclear weapons states back to the negotiating table on issues of nuclear nonproliferation, moving the world away from the era of “good faith” negotiations under the NPT. Those in support of the treaty anticipated a negative reaction from the nuclear powers, and while they consider the treaty “a good starting point for changing perceptions”, they did not expect these countries to sign right away.

While the treaty itself will not immediately eliminate any nuclear weapons, the treaty can, over time, further delegitimize nuclear weapons and strengthen the legal and political norm against their use. -Daryl G. Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association

Further reading

United Nations section about the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

What is the difference between signature, ratification and accession of UN treaties?

Voting on UN resolution for nuclear ban treaty. December 23, 2016. ICAN.

Joint Press Statement from the Permanent Representatives to the UnitedNations of the United States, United Kingdom and France following theadoption of a treaty banning nuclear weapons. July 2017.

Chronology of U.S.-North Korean Nuclear and Missile Diplomacy. Arms Control Association.

The Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty: reasons for scepticism. The NATO Review Magazine. May 19, 2017.

Bolton M and Minor E. (2016) The Discursive Turn Arrives in Turtle Bay: The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons’ Operationalization of Critical IR Theories. Global Policy. DOI: 10.1111/1758-5899.12343.

Why Are Biological and Chemical Weapons Prohibited, But Not Nuclear Weapons? Foreign Policy in Focus. April 11, 2016.

Banning nuclear weapons without the nuclear armed states. Article 36. Briefing paper. October 2013.

Filling the Legal Gap: The Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Article 36. April 2015.